“The international community failed Rwanda, and that must leave us always with a sense of bitter regret and abiding sorrow. If the international community had acted promptly and with determination, it could have stopped most of the killing. But the political will was not there, nor were the troops.”

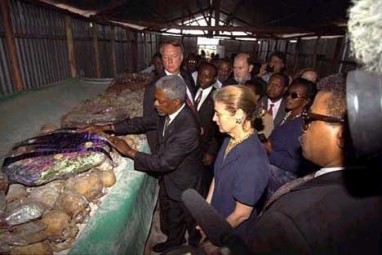

Kofi Annan, New York Memorial conference on Rwanda, March 26, 2004.

For the 10th anniversary of the genocide in Rwanda in April 2004, the General Assembly adopted resolution 58/234 on December 2003, which mandated 7 April the International Day of Reflection on the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda. While survivors commend this important international public acknowledgement, the UN should consider marking the genocide with more than just a commemoration.

In fact the United Nations General Assembly has consecutively issued resolutions calling for UN agencies to provide support for survivors, but such calls have largely gone unheeded. Resolution 59/137 in 2004 called for “Assistance to Survivors of the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda” and has been readopted at consecutive General Assemblies, including most recently in December 2011 with resolution 66/228 calling for “the Secretary-General to continue to encourage the relevant agencies, funds and programmes of the United Nations to implement resolution 59/137 expeditiously, inter alia, by providing assistance in the areas of education for orphans, medical care and treatment for victims of sexual violence, including HIV-positive victims, trauma and psychological counselling, and skills training and microcredit programmes aimed at promoting self-sufficiency and alleviating poverty.” But to date the resolution has yet to be meaningfully honoured. In fact, there is no framework for restorative justice for survivors of the genocide, either in Rwanda or internationally.

The cumulative annual funding from UN agencies, funds and programmes for survivors’ in Rwanda amounts to less than $250,000 USD (less than $1 USD of aid per survivor). In contrast, the appropriation of UN funds for the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) for 2012-13 through resolution 66/238 is $183 million USD. In total, expenditure on the ICTR has amounted to over $1 billion USD (equivalent to almost $30 million USD per suspect convicted). As such, the total sum of support for restorative justice programmes in Rwanda has amounted to less than one-half of one per cent of the ICTR budget.

The lack of action by the ICTR and the UN in regards to support for Rwandan genocide survivors is in stark contrast to steps taken by the ICTR’s ‘sister tribunal’, the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY). The calls of former ICTY President Robinson for the establishment of a trust fund for victims led to, in 2011, an arrangement between the ICTY and the International Organisation for Migration to carry out a “comprehensive assessment study aimed at providing guidance to the Tribunal on appropriate and feasible victim assistance measures and possible means of financing.”

This study is preceded by the mandate of the International Criminal Court (ICC) which through Article 75 of the Rome Statute (1998) allows for enforcement of restorative justice for survivors of human rights violations. The Trust Fund for Victims (TFV) is the main mechanism for doing so, along with the ICC’s legal mandate to require convicted individuals to compensate victims with their own assets which it does in DRC and Uganda. However, there is no such mechanism at the ICTR. This has been recognised as a serious shortcoming by a number of its presidents, most recently Judge Byron, who stated that “the fact that it [ICTR] could not provide reparation to victims will forever be a stain on its reputation.”

This is in light of the fact that the UN did not prevent the genocide, nor did it stop the killing once the genocide had begun, in spite of the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The UN Security Council has accepted responsibility, and a number of critical actors involved in the decisions taken at the time of the genocide, including the Belgian Government and President Clinton, have apologized. Though to date, this has not translated into meaningful support, deeply affecting survivors.

By committing meaningful support to survivors of the genocide in Rwanda, the UN will secure the legacy and the very first objective of the ICTR to challenge impunity and deliver justice to victims.