By Glory Iribagiza, The New Times

It was around 2:30 pm when Pierre-Claver Karenzi’s home telephone rang. It was the killers’ call and the news were none other than what he already knew was coming.

“We are coming to kill you with your family,” one of them said.

It was on April 21, and it was a surprise that the family was still alive, given that the Genocide against Tutsi had started weeks before in other parts of the country.

Just the day before, the last Queen of Rwanda, Rosalie Gicanda, had been killed in Butare, something believed to have been the official launch of the Genocide in that area. If the queen could be killed, who would be spared?

Karenzi and his family which lived with him in Butare had been spending nights in the farmland and only tip-toeing into the house in the morning.

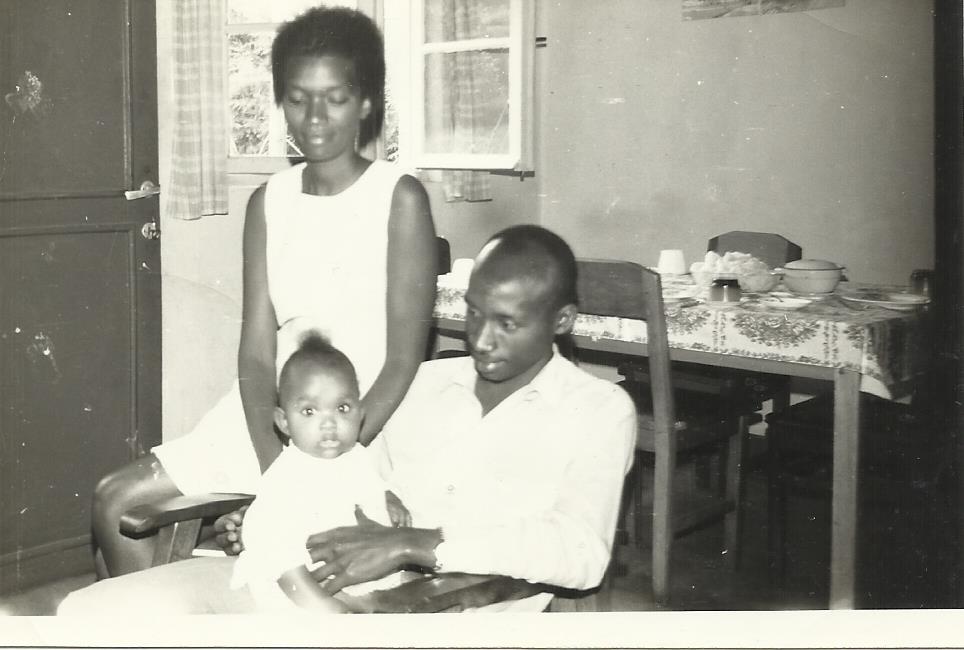

He was married to Alphonsine Mukamusoni with whom they had three children; Solange Karenzi who was 22, Malik Kabaya who was 19, and Christian Mulinga who was 15.

Their friend who lived in Kigali, Fidele Kanyabugoyi had sent his two children, Emery Songa and Thierry Bahizi to live there when the Genocide started, hoping they would survive from Butare where killings delayed to start.

They also had their niece, Seraphine Umukamisha who was 17 living with them, and Yvette Umugwaneza, a friend to their firstborn who was also her colleague at work.

When Karenzi was given the notice on telephone, he and his wife Mukamusoni immediately called the children so they could hide them in the ceiling.

The opening to the ceiling was not big enough, so they had to force them in one by one. It was not easy to carry all the seven, and some of them, like their firstborn, Solange, had really grown and were heavy.

The killers, who consisted of soldiers from the presidential guard unit arrived at the house when the last child just entered the ceiling! They did not notice.

They immediately took Karenzi and Mukamusoni in front of Hotel Faucon located in Butare’s town where other Tutsi people had been gathered.

After a short while, Mukamusoni was released and she returned home, not knowing a soldier had followed her home.

After a few minutes, before she even sat to digest what had happened to her, he entered.

He told her to give him money, but she told him she didn’t have any.

He insisted that he would take any amount, but she told him if he wanted, he would take her husband’s company car.

“It is ours anyway. Do you know I can kill you now?” The soldier asked, but Mukamusoni told him to do whatever he wanted.

He immediately shot her and left her dead.

The children heard everything from where they hid. They climbed down from the ceiling and found Mukamusoni’s body on the floor and covered it quickly with pieces of cloths.

They decided to sneak out to hide in their neighbour’s banana plantation where they spent a night until they left in the early morning of April 22 to seek refuge in a convent, Benebikira, in Taba.

After eight days at the convent, soldiers from Camp Ngoma, Interahamwe, residents of Butare and some lecturers who worked at the former National University of Rwanda attacked the convent and picked all the seven children and 24 other people from other refugees and killed them.

In all the children who were from Karenzi’s house, only one, Yvette Umugwaneza survived. She is the one who narrated the story to Karenzi’s relatives who include Gasana Ndoba, who lived in Europe at the time of the Genocide.

The family also later learnt that Karenzi was shot several bullets after torturing him. He was kneeling in the street, just in front of Faucon.

“He was killed in the main street of Butare town for all people to see. He was well known, and people who saw the scene told us that the killers wanted to show a sign that even the well-behaved Tutsi people had to be killed,” Gasana said.

He added that the killers said that people should come and see how the brain of a Tutsi person looks like.

His body stayed there for around three days until the killers took it to a place no one has found out to this minute.

Karenzi was a lecturer of physics and related subjects at the University until he was killed in the 1994 Genocide against Tutsi.

He was the only one among his siblings who lived in Rwanda. Others were in Burundi, DR Congo, Canada and Europe.

Karenzi’s nucleus family is just one of the many thousands that were completely wiped out during the Genocide. These families will be remembered on Saturday, June 4.

A family is considered wiped out when both parents and all the children in the household are killed.

The most recent count that was concluded in 2019 indicate that there were 15,593 completely wiped out families comprising of 68,871people.

Every year since 2009, the Alumni of Genocide Survivors’ Students Association (GAERG) holds memorial events for families like Karenzi’s, that were not survived, with the theme “Ntukazime nararokotse” (Never be forgotten when I survived).

“We tell those we remember that we miss them, we miss the good moments we shared, and we remember how they were killed. We promise them that we will always remember them and that we will try to fill their gap, although it is hard.

We also tell them that the Inkotanyi they used to love eventually stopped the Genocide, and that Rwanda is now peaceful,” Egide Gatari, the president of GAERG told The New Times.

He added that the memorial is a reminder to the world to take serious measures against discrimination that would lead to genocide, so that no more families have to be wiped out again.

Karenzi is remembered to have been a researcher on human development activities. His brother, Gasana, has been gathering his theses and books that used to belong to his home library. He has gathered more than 1,000 so far.

He was a family man, despite his busy schedule. He loved making breakfast for his family, making his children’s beds and playing with them.

He also loved football, reading, and people. His home library was always filled with his students, his daughter’s classmates and neighbours.

Karenzi rallied people in Butare to build for themselves the first private secondary school in the region (CEFOTEC), because Tutsi children were discriminated against and oftentimes not afforded their right to education.

It is also where two of his children were studying.

Gasana is working on a documentary and other projects so that this family will never be forgotten “as long as humans still exist.”