A guest post by Albert Gasake, Legal Advocacy Coordinator of Survivors Fund on reflections on Article 8 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the right to effective remedy for survivors of the 1994 Tutsi genocide in Rwanda to mark Human Rights Day

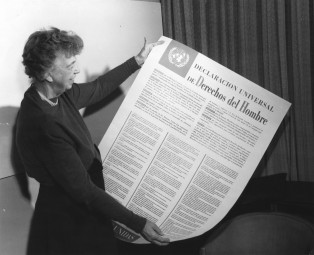

Today marks the 64th anniversary of the adoption and proclamation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which Human Rights Day marks each year on 10th December.

The UDHR came into effect in the immediate aftermath of the Holocaust and World War II, on December 10, 1948. The international community vowed to never again allow such atrocities. Despite this remarkable commitment and milestone, the 1994 genocide in Rwanda was not prevented, resulting in the killing of over one million people. Over 400,000 people survived the genocide, and continue to live, and die, from its consequences today.

We should not reiterate the uncontested role of the international community and the flagrant breach of both the UDHR and UN charter itself in failing to stop the genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. This has been largely documented and for which the UN has accepted responsibility. Rather, our utmost hope, which is shared by the victims’ expectations of the UN, is to enact further steps to translate this acceptance of responsibility into concrete action to deliver to survivors some form of restorative justice. The failure to take such a step risks sending signals of consistently empty gestures to victims and gravely undermining the reputation of the UN.

As the world marks Human Rights Day, we look briefly to the famous and often controversial International Bill of Human Rights, to which virtually all countries, including Rwanda, has largely incorporated into domestic clauses and signed into national legislations. An area of controversy is that some commentators claim its abstract discussion of human rights demotivates people from upholding the values that the rights are meant to affirm.

One of the provisions of this historic document is worth addressing further; Article 8, which promotes victims right to effectively remedy their lives, is a topic that has currently raised a variety of concerns and unprecedented impasse between the survivors’ community both in and outside the country, as well assume of the decision makers in Rwanda. We would like to shed light on how this article has or has not been realized in post-genocide Rwanda, as well as internationally, in its attempt to provide survivors with effective remedies to the harsh aftermath of the 1994 genocide. Article 8 states that:

‘’Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted him by the constitution or by law’’

A a matter of legal right, and in line with the recent human rights instrument, Article 8 grants victims the right to effective remedies which includes restitution, compensation, rehabilitation, satisfaction, and guarantees of non-repetition. Guided by this provision, the UN Basic Principles and Guidelines on the Right to a Remedy and Reparation for Victims of Gross Violations of International Human Rights Law and Serious Violations of International Humanitarian Law sets out a comprehensive roadmap for realizing victims’ right to remedy, with which all nations, including Rwanda, should comply.

Although the Constitution of Rwanda is largely inspired by the UDHR, the application of this provision to secure the right to reparations for genocide victims remains problematic at best. Since 1996, genocide perpetrators have been brought to account for their actions in Rwanda’s courts. As a result, over 4,000 individual survivors have awarded compensation in such cases, but the majority of these judgements have never been enforced. With the inception of gacaca courts, the right to effectively remedy victims of genocide, unlike victims of ordinary crimes, was considerably reduced in Rwanda’s legislation.

The government argues that it established a fund to support the most vulnerable survivors (FARG) to which it contributes 6% of its annual budget. Some decision assumes that effective remedy means paying for the dead which would not be “dignifying.” This is perhaps due to a narrow interpretation of the notion of reparation.

It is worth noting that human rights violations committed against survivors of genocide are irreparable. Nothing will restore a victim to the status quo after the horrendous suffering they experienced such as rape, torture and humiliation, loss of a parent, a sibling or a spouse. We recognize that no amount of money and no combination of benefits can erase either such experiences or such consequences. This, however, should not be an excuse for inaction. The legal provisions on effective remedy for victims as inspired by UDHR have limited capacity to provide even the legal minimum in order to honor the memory of the dead and restore the lives of survivors. This legal minimum is exactly what genocide victims rightfully expect from the government, and one that should have an effective, established framework which prompts action, not just ideals.

While the government has undertaken considerable efforts in supporting survivors through FARG, it should be clear that FARG does not equate or exclude survivors’ rights to effective remedy. The main criticism of why FARG does not constitute reparation is that it is a programme, which despite specifically targeting support to survivors, does not link the services provided to any sort of recognition of the suffering of survivors as a result of the genocide. This is a social service that the government should be providing anyway, but is now labeled as reparation rather because it is convenient to do so. Furthermore, survivors were either entirely uninvolved or play only a minimal role in the development and governance of FARG, and so their perspectives are not reflected in it.

The UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (UNICTR) was established to bring “big fish” to justice. Unlike the International Criminal Court (ICC), the ICTR did not recognize the right to effective remedy for victims in line with Article 8 of the present declaration. In fact, of over 75 accused perpetrators tried before ICTR, not one victim has ever been allowed to step in on the proceedings to file a reparation claim. Lack of a mandate for effective remedy is the reason for this shortcoming. This failure confirms the criticism that the international community’s main concern in setting up the UNICTR was not primarily eradicating impunity and rendering justice to victims following the 1994 genocide as it was claimed, but rather to work on its image stained by the failure to stop “the preventable genocide.”

Therefore, as we celebrate 64th anniversary of the UDHR, in relation to the survivors of the genocide in Rwanda, they are still awaiting for Article 8 to be meaningfully honored by both the Government of Rwanda and international community. The UDHR lays down obligations that States are bound to respect. Article 8 is one of those obligations which has yet to be honored, to the unfortunate consequence of the hundreds of thousands of Rwandan survivors. By becoming parties to international treaties, States assume obligations and duties they must respect under international law, most importantly to protect and to fulfill human rights, including rights to remedy for victims.

The right to effective remedy is interdependent and indivisible of justice itself. The improvement of one right facilitates the advancement of the others. Likewise, the deprivation of one right adversely affects the others. After 18 years, we believe that it is high time for both the Government of Rwanda and the international community to realize survivors’ right to reparation and fulfill their obligations by setting up a reparation fund for survivors. There can be no more excuses or reason for delay.

As such, we call for this Human Rights Day to serve as a reminder and catalyst for prompt action so that survivors may finally have the opportunity to remedy their lives post-genocide, as they so desperately deserve, and which is their right.

Albert Gasake is the legal advocacy coordinator at Survivors Fund (SURF)