Despite Challenges, Genocide Survivors Feel More Hopeful Today – Ibuka Chief.

Interview by Eugene Kwibuka, The New Times.

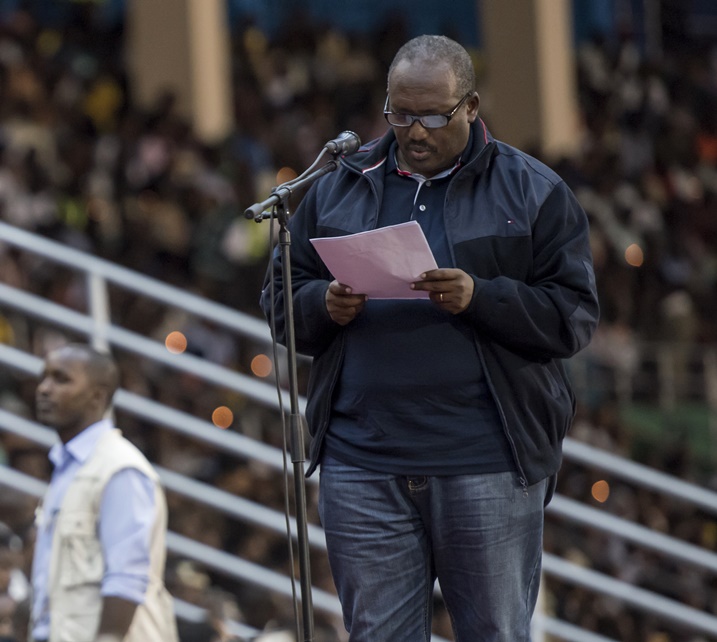

Rwandans and friends of Rwanda across the world last week started a week-long commemoration of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi.

In an exclusive interview, Prof. Jean Pierre Dusingizemungu, President of Ibuka, the umbrella organisation for Genocide survivors in Rwanda, spoke to The New Times’ Eugene Kwibuka about the general feeling for the Genocide survivors, 22 years after the end of the tragedy.

Below are the excerpts:

We are commemorating the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi for the 22nd time, what is the general feeling for many survivors living in Rwanda and those in Rwandan communities abroad?

What I can tell you is that as years go by since the end of the Genocide, the more there is improvement for Genocide survivors in terms of what other people tell them and the help they get. Right now, we feel that genocide survivors are stronger and more ready to participate in the events to commemorate the genocide because there were efforts to prepare them for the tough mourning period. We have to find strength to go through the mourning period and we always talk to each other as genocide survivors so that we can be ready to commemorate the genocide year after year.

So, we would say that genocide survivors now feel emotionally stronger than in the past years?

Yes, they feel stronger given the positive messages they get every day through their leaders and the media, especially in terms of preparing them for the mourning period. Apart from getting ready for the mourning period, we also have a general feeling that there were many good things that were done for genocide survivors by the government and other institutions to help them deal with genocide consequences. The initiatives to help genocide survivors have been increasing over the past few years and they give survivors hope and a positive feeling about life.

In their most recent assembly last month, members of Ibuka resolved to fight genocide and genocide ideology. How much of a threat is genocide ideology for survivors today?

It’s a big threat because there are signs that genocide ideology is still there, which means that genocide can happen again if we don’t do something to discourage the ideology. The problem is that those who committed the genocide and their supporters such as some colonialists are interested in promoting the genocide ideology because they were not happy when the genocide was stopped by the Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF). So, when the genocide was stopped, those who had supported it continued to nurture hatred among people and they have proceeded to denying that the genocide happened. When we realise that such ideas to promote hatred and denial of the genocide are still there, it makes us worried because it shows that genocide ideology isn’t eradicated yet and we have to do something to fight it so that genocide doesn’t happen again.

How does Genocide ideology manifest itself today in Rwanda and abroad?

By the way, because we have laws that punish genocide ideology in Rwanda people who have the ideology try to find a hidden way of expressing it. So, what we have got today are people who resort to stigmatising genocide survivors by calling them names and branding them as people who are too traumatised to be useful in society.

For instance, people with genocide ideology can easily brand all genocide survivors as drug addicts after meeting only one genocide survivor who abuses drugs. That kind of stigma and stereotypes can make it hard for survivors to get jobs in society and you find that those who promote genocide ideology have smart and metaphorical ways of making life for genocide survivors more difficult through promoting stereotypes against them.

We need to be aware of the hidden mechanisms used to stigmatise genocide survivors so that we can fight them.

As for genocide ideology in foreign countries, the issue is much more complicated because many of the countries don’t have laws to punish genocide ideology. Some of the countries have laws against denial of the genocide against the Jews (the Holocaust) but they have no laws to punish denial of the genocide against the Tutsi, which makes it difficult to sue deniers of the genocide against the Tutsi. That’s a big challenge for us indeed.

Let’s talk about welfare for genocide survivors. What’s the biggest challenge for genocide survivors in terms of welfare today?

When we talk about welfare for genocide survivors, for us we are concerned about vulnerable and poor genocide survivors. The main challenges for these people are finding shelter, education, and healthcare. The government has heavily invested in solving these challenges but the needs are still overwhelming because of the devastating consequences of the genocide. For example, some of the homes that were initially built for genocide survivors are now too old and need to be renovated. Some of the houses were poorly built because it was urgent to find a home for survivors but they are now falling apart or simply need to be completed. Right now, the fund for support of Genocide survivors (FARG) estimates that at least Rwf23 billion is needed to repair dilapidated homes of genocide survivors and build new ones. It’s a challenge because that’s a lot of money but we have to find a solution.

How does Genocide ideology manifest itself today in Rwanda and abroad?

By the way, because we have laws that punish genocide ideology in Rwanda people who have the ideology try to find a hidden way of expressing it. So, what we have got today are people who resort to stigmatising genocide survivors by calling them names and branding them as people who are too traumatised to be useful in society.

For instance, people with genocide ideology can easily brand all genocide survivors as drug addicts after meeting only one genocide survivor who abuses drugs. That kind of stigma and stereotypes can make it hard for survivors to get jobs in society and you find that those who promote genocide ideology have smart and metaphorical ways of making life for genocide survivors more difficult through promoting stereotypes against them.

We need to be aware of the hidden mechanisms used to stigmatise genocide survivors so that we can fight them.

As for genocide ideology in foreign countries, the issue is much more complicated because many of the countries don’t have laws to punish genocide ideology. Some of the countries have laws against denial of the genocide against the Jews (the Holocaust) but they have no laws to punish denial of the genocide against the Tutsi, which makes it difficult to sue deniers of the genocide against the Tutsi. That’s a big challenge for us indeed.

Let’s talk about welfare for genocide survivors. What’s the biggest challenge for genocide survivors in terms of welfare today?

When we talk about welfare for genocide survivors, for us we are concerned about vulnerable and poor genocide survivors. The main challenges for these people are finding shelter, education, and healthcare. The government has heavily invested in solving these challenges but the needs are still overwhelming because of the devastating consequences of the genocide. For example, some of the homes that were initially built for genocide survivors are now too old and need to be renovated. Some of the houses were poorly built because it was urgent to find a home for survivors but they are now falling apart or simply need to be completed. Right now, the fund for support of Genocide survivors (FARG) estimates that at least Rwf23 billion is needed to repair dilapidated homes of genocide survivors and build new ones. It’s a challenge because that’s a lot of money but we have to find a solution.

Then there are properties for notable genocide criminals and convicts which need to be well managed because they need to be sold to pay damages for genocide survivors. Some of the properties could be sold by the owners or transferred to new owners before they are seized in the interest of survivors. We need to watch out for that.

People should also know that genocide fugitives are still at large around the world. Why aren’t they being arrested? Why can’t governments in countries where they live arrest them and bring them to justice? Notorious genocide suspects like Félicien Kabuga, Fr. Wenceslas Munyeshyaka, and many more are still roaming free and we need political will worldwide to arrest them.

Finally, there is an issue of genocide convicts tried by Gacaca courts who are completing their sentences and will soon be going back home en masse to live with the rest of people in their communities. We are wondering how these convicts and people who will receive them back in communities are being prepared to live together in society. The government needs to set up programmes that educate the survivors, the perpetrators’ families, and the convicts themselves how to live together in society.

Again, we need to continuously deal with the consequences of the genocide and we should keep explaining the laws against genocide ideology so that people don’t resist in respecting them.

As we conclude our interview, feel free to share with our readers any other message you would like them to know as we mark the 22nd anniversary of the Genocide.

People need to know that it’s important to commemorate the genocide and we should all take part in commemoration activities in our families and communities. The mourning period is crucial for our own healing and our children’s education. They need to grow up with the habit of commemorating the genocide and understanding that it’s important for their own development. We also need to support each other during the commemoration and help those who are most in need, especially genocide survivors.